KCRW’s acclaimed music documentary podcast, Lost Notes, returns for its fourth season. Co-hosts Novena Carmel (KCRW) and Michael Barnes (KCRW / KPFK / Artform Radio) guide you through eight wildly different and deeply human stories, each set against the kaleidoscopic backdrop of LA’s soul and R&B scene of the 1950s-1970s. Support KCRW’s original programming like Lost Notes by donating or becoming a member.

Lost Notes explores how Fela Kuti’s time in LA in 1969 was instrumental in the creation of his legendary Afrobeat sound.

Michael Barnes

By the dog days of the summer of 1969, the then-unknown Nigerian musician Fela Kuti and his band were crawling to the end of their first American tour. They’d been ripped off by their promoters. They were completely out of money. And, worst of all, their visas had expired during the tour … so they were stuck here in Los Angeles, laying low from the Feds.

Novena Carmel

It was indeed a desperate situation. But folks might want to know how they got there in the first place.

Michael Barnes

Well, there are lot of ways into this story … but since Fela is often thought of as the “African James Brown,” perhaps it’s good to start off with Soul Brother #1, Mr. Dynamite himself: James Brown.

Michael Barnes

While James Brown wasn’t the first soul artist to make inroads into Nigeria and West Africa, it’s safe to say that no other performer had the impact that he did.

Novena Carmel

That’s absolutely true. By the mid-’60s, James Brown’s influence was pretty much everywhere in West Africa. And Nigeria was no exception.

Michael Barnes

Brown himself didn’t tour the African continent until the end of 1970. But in the meantime, local bands were recreating their own versions of the James Brown experience.

Novena Carmel

Yeah, it’s really fascinating, too. All of a sudden, throughout West Africa, you had what they called “copyright bands.” These bands were devoted to playing note-perfect renditions of the popular music of the day. And because the original artists weren’t touring the continent yet, it was a way for folks to be in the room with that music, feeling it, the way it was meant to be experienced… or, y’know, as close as possible to the real thing. And for a period of time in the late ‘60s, the copyright bands took over the West African music scene.

Michael Barnes

But Fela wasn’t into the copyright band scene at all. He’d spent the last few years trying to make his own thing happen. But the copyright band scene wasn’t the only thing happening in West Africa. Highlife music was also huge at this time.

Novena Carmel

Highlife had been the popular music of West Africa for decades. In the beginning, it had more of a big band sound, sort of like a mashup between melodies and rhythms from local cultures, with European military brass band stylings. But later on, African musicians incorporated rhythms from American Jazz, Trinidadian & Jamaican Calypso, and Afro-Cuban Mambo. You had Cha-cha, you had Rumba in the mix. A beautiful synergy of sounds from all over the African Diaspora.

Michael Barnes

In fact, if you’re familiar with Afro-Cuban music, you’ll hear the 2:3 and 3:2 clave patterns in Highlife, but in many cases it’s not a clave that you hear, but what the clave was originally based on in Africa: the Ghanaian bell called the gankogui, which is used in music throughout West & Central Africa. And since Nigeria in particular was fighting for its independence during this time, highlife became the soundtrack for that struggle: the sound of both celebration and of national pride.

Koola Lobitos, Fela’s first band, in 1965. Photo courtesy Fela Kuti estate

Novena Carmel

And it’s in this spirit – particularly inspired by the King of Highlife, trumpet player and bandleader E.T. Mensah – that Fela forms his first band, Koola Lobitos. And when you listen to their early recordings, that sweet highlife sound is front and center.

Michael Barnes

But Fela’s musical education in England also puts him into contact with modern jazz for the first time. He falls in love with Hank Mobley and Harold Land and Herbie Hancock. And even though he hasn’t figured out how to incorporate it into his music yet, it expands his sense of what’s possible. And, over time, he develops this new music called “highlife jazz.”

Novena Carmel

But Nigerian audiences are not sure what to make of this “highlife jazz.” Fela took the highlife music they already loved and, frankly, added too much jazz! Too much information. It was just a lot for them. And he was also extremely threatened by the “copyright bands,” who were tearing up the scene from Ghana to Nigeria and beyond … and putting him out of work in the process.

Michael Barnes

One artist in particular was getting under Fela’s skin: a guy named Geraldo Pino from Sierra Leone. He first came to Lagos in 1966. And Fela went to the show, and left it very impressed by Pino’s showmanship. He even said that seeing Pino “made me fall right on my ass.” DAMN!

Novena Carmel

(laughs) Damn!

Novena Carmel

Pino put on an amazing show. And he was a really savvy entertainer. He and his band, the Heartbeats, mastered lots of other styles before taking on James Brown. And as impressed as Fela was by the spectacle of what he was doing, I think he resented that so many musicians were having so much success impersonating someone else, while he was out there trying to invent his own thing.

Michael Barnes

As frustrating as it must have been for Fela, I think the runaway success of those bands forced him to look at his own identity in a more conscious way.

Novena Carmel

Absolutely. I mean, he had a negative reaction to what he saw as the phoniness of the copyright bands. But I also think he could see that his own music – “highlife jazz” – wasn’t connecting with people in the way that he wanted it to. And that realization is what pushed him into finding a new sound. One that was uniquely African. He actually said he wanted his music to be “a pride to the black race.”

Michael Barnes

And so he came up with a new term: Afrobeat. And he even alerts the press to announce that his sound will now be called Afrobeat.

Novena Carmel

But at first, the sound of his music doesn’t really change, even though he gives it a new name. He essentially changes the brand name, but not the product. And It certainly doesn’t sound like the Afrobeat we know today. So, how and when does the music itself change? Well, that story kicks off in May of 1969, in the Arrivals lounge at JFK Airport.

Michael Barnes

It’s important to remember that there wasn’t really a “world music” scene when Fela arrived stateside in 1969 and the few successful African artists operating in the United States were considered outliers. Nigeria’s Babatunde Olatunji had recorded with jazz legends Max Roach & Randy Weston, plus releasing his own albums. And by 1967, South Africa’s Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba both had enjoyed chart hits. But otherwise, at least as far as mainstream American audiences were concerned, music from the African continent was the stuff of Disneyland’s Adventureland or perhaps Folkways’ field recordings.

Novena Carmel

At the same time, the psychedelic movement of the late ‘60s had begun to embrace African polyrhythms. That’s why, at Woodstock later that year, you see artists like Richie Havens, Santana, and Jimi Hendrix incorporating so much percussion into their sets. And America was still the birthplace of all that soul and R&B that had become so popular in West Africa. In Fela’s eyes, America represented a wellspring of untapped opportunity for African artists. So when he’s offered a chance to tour the States in 1969, he saw it as the break that could wipe his rivals off the map for good.

Michael Barnes

But trouble was brewing before Fela and his band had even gotten to the US. The promoter who made the initial offer ended up having to borrow money from his own brother to pay for the band’s flights to New York. And when the band landed at JFK in May, their American promoters were nowhere to be found. Instead of a full itinerary, they only had three confirmed gigs for the entire tour – in Washington D.C., Chicago, and San Francisco – and then to top it all off, they ended up having to drive cross-country to their shows, all at their own expense!

Novena Carmel

Musically, though, Fela and his band were really cookin’, sounding tight. And he was determined to impress whoever he could, whenever he could. And a few of their higher-profile performances actually seemed like they could give the band the career lift they so badly wanted.

Michael Barnes

Indeed. Y’know. at one of their early shows in California, Lou Rawls showed up with his friend and collaborator, H.B. Barnum. Barnum was a superstar arranger and producer. He’d worked with Diana Ross and the Supremes, Sammy Davis Jr., Nancy Wilson, Cannonball Adderley, and so many more. And, based on what he saw and heard that day, he wanted to offer Fela a recording contract … as well as a series of high-profile concerts at – wait for it – Disneyland.

Novena Carmel

A version of the story we’ve heard is that Disney wanted Fela to perform in the park’s Adventureland attraction. But, in the end, they judged that his music wasn’t African enough.

Michael Barnes

Fela wasn’t African enough.

Novena Carmel

Yep! Walt Disney knows his stuff.

Michael Barnes

Yeah. I mean, when I think of an expert on African music … Walt Disney. First name that comes to mind.

Novena Carmel

The picture of expertise, indeed. Anyway, none of it mattered, because Fela’s absentee tour promoters somehow get wind of this offer. And they reappear and threaten to sue Fela for breach of contract if he signs with Barnum. So the deal falls through … which is maybe for the best in this moment … and those shady promoters disappear into the ethers once again.

Michael Barnes

By now, it’s nearly August, and Fela and the band are broke and exhausted. They end up crashing at a friend’s spot in Inglewood until they can figure out their next move. Fela reaches out to a club in Hollywood to arrange some shows … but once again, his deadbeat tour promoters intervene. And this time, they take things a step further: they call immigration authorities and report Fela and his band for overstaying their visas – despite the fact that the promoters were supposed to be their custodians!

Novena Carmel

Lord. Your face right now, Michael.

Michael Barnes

The audacity of these people!

Novena Carmel

So now Fela is in a tailspin. He manages to get an extension on their visas before the entire band is forcibly deported … but they’re still stuck in L.A., with no way to get home or to even make a living in the meantime.

Michael Barnes

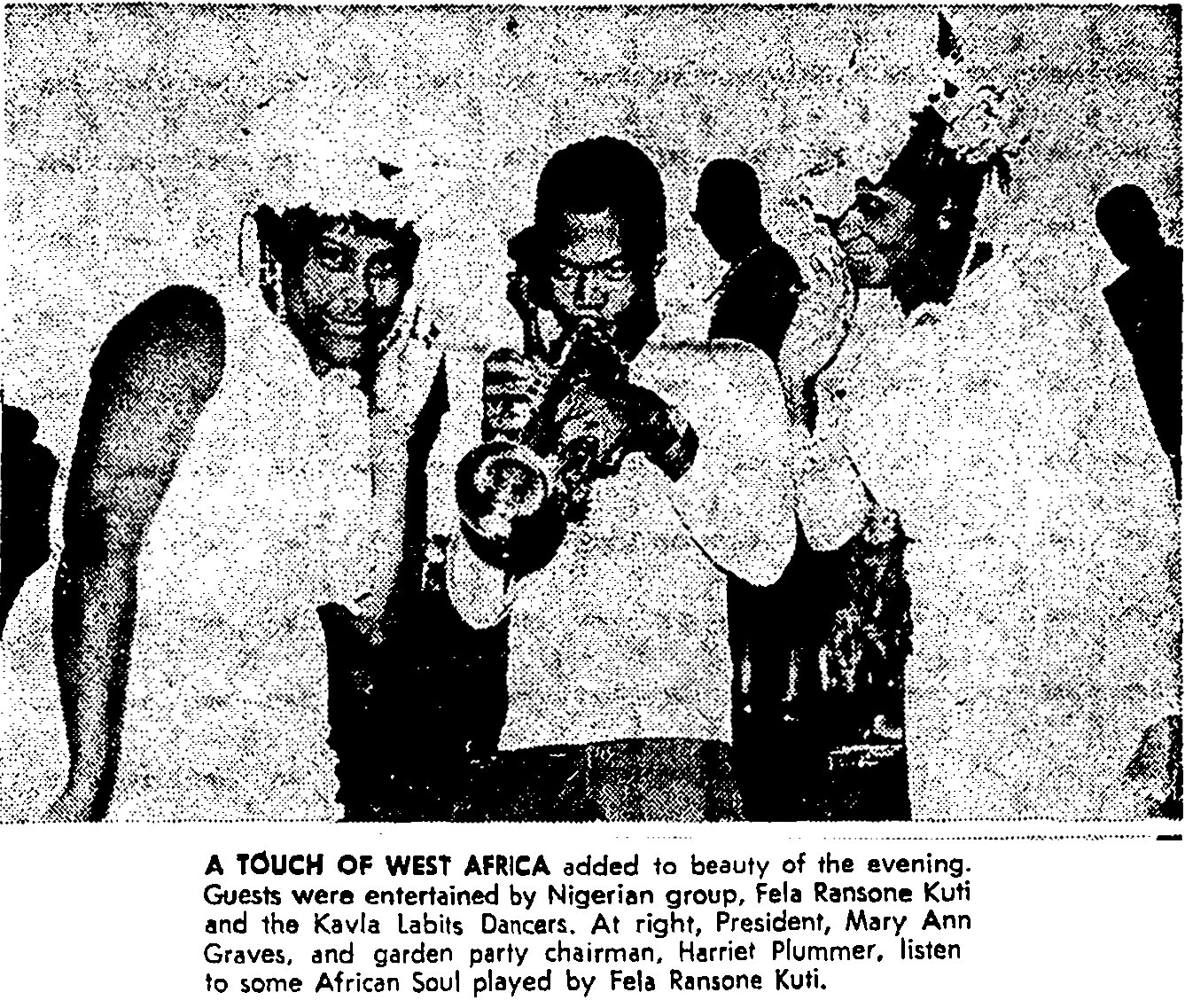

But just as it seems they’ve hit rock bottom, things finally take a turn. Fela makes a connection with the Regalettes, a Black women’s fundraising and social club based in Los Angeles. And through them, he secures an invitation for the band to perform at their annual fundraiser in the Palm Garden of the Ambassador Hotel on August 3. There’s even a photograph of Fela, flanked on each side by the Regalettes’ president and their garden party chairman in the Los Angeles Sentinel a few days later. No one could have known it at the time, but this photo captures Fela just as his life and his music is really about to change.

Fela at the Ambassador Hotel on August 3, 1969, with the Regalettes’ Harriet Plummer (L) and Mary Ann Graves (R). Photo via LA Sentinel archives.

Novena Carmel

As with Fela’s earlier appearances in the LA area, this one was attended by members of the Black musical and social elite – including Juno Lewis, who is the percussionist and poet who wrote and recorded “Kulu Sé Mama” with John Coltrane in 1965. Lewis’s piece is based around a long poem he wrote expressing pride in his African ancestry – so he probably very intentionally made a point of befriending Fela when he came to town.

Michael Barnes

As we mentioned earlier, it wasn’t every day that African artists were touring the States back then. And Fela himself wasn’t yet aware of the massive symbolic power that Africa exerted on Black American consciousness during this time. So, his appearance must have been a real event for this audience, people who would have been actively engaged in all that discourse around African and African-American identity.

Novena Carmel

There was a young woman in the audience named Sandra Smith, who later changed her name to Sandra Izsadore. And she came to see Fela perform at Juno’s invitation. She was born and raised in Los Angeles and became a Black Panther and a student of the Nation of Islam while still a teenager. But Fela, he didn’t know any of this when he saw her from the stage. All he knew was, his interest was more … socially-oriented, shall we say.

Michael Barnes

“Socially-oriented” … love it. Between sets, Fela finesses an introduction to Sandra through Juno. Sandra remembers that the first thing Fela did was to ask if she had a car. When she said that she did, he replied: “Good. You’re going with me.”

Novena Carmel

In her own car. (Laughs)

Michael Barnes

In her own car. But Sandra was young, and she said that she actually found his arrogance intriguing. Fela was an opportunity to expand her own education around what Africa meant from an African perspective. But, at least as far as Fela was concerned, she learned that Africans and Black Americans had very little common ground in their ideas about what Africa represented.

Novena Carmel

According to Fela, while Black Americans wore traditional African fabrics and played talking drums, Africans at the time were embarrassed by those things. Africans wanted to, in their eyes, modernize and to compete with their former colonizers on the world stage. And it shocks Sandra to realize that Fela had a rose-colored view of Black folks’ lives in the United States.

Fela Kuti and Sandra Izsadore in an undated photo. Photo courtesy Fela Kuti estate.

Michael Barnes

So Sandra and Fela embark on this somewhat unlikely relationship in which she becomes his teacher. She introduces him to the philosophy of the Black Panthers, writings from Frantz Fanon like Wretched of The Earth, and gives him a copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X – all of which truly raise his consciousness. The Autobiography of Malcolm X in particular revolutionizes his understanding of not only Black Americans’ history, but also his own. While reading it, Fela said, “Everything about Africa started coming back to me.”

Novena Carmel

It really does say something about how much of life is context. Because Fela came from a long line of politically engaged people. Both his grandparents and his parents were deeply involved in issues around labor activism, education, feminism, nationalism … I mean, his mother in particular even had a staggering list of achievements which would take a whole episode to talk about. But even up until this moment, Fela claimed he was not a political person himself.

Michael Barnes

What’s even more interesting is how meeting Sandra seems to also galvanize his musical philosophy. You’ll remember that Fela had been yearning for a new kind of music with a uniquely African identity and perspective. And maybe there’s an irony that he had to come to Los Angeles to unlock this more authentic vision of his music … but that is absolutely what happened.

Novena Carmel

You know, I also think it comes down to a fundamental shift in perspective – from those ego-driven goals that he had of becoming the best musician, the most popular bandleader, all these titles, you know, that depended on the outside world giving him something … to then this more expansive sense of who he is in the world. Fela had been inspired to become a messenger of ideas, and he was reinvigorated to apply himself as a serious artist.

Michael Barnes

And there was another major influence on Fela at this time as well: marijuana. Although Fela had first tried cannabis during his college years in London, it became a cornerstone of his life in L.A. Fela would later comment on how much it helped him to get out of his own way, both as a performer and as a composer. And as anyone who has smoked weed can tell you, it definitely affects the way you hear music.

Novena Carmel

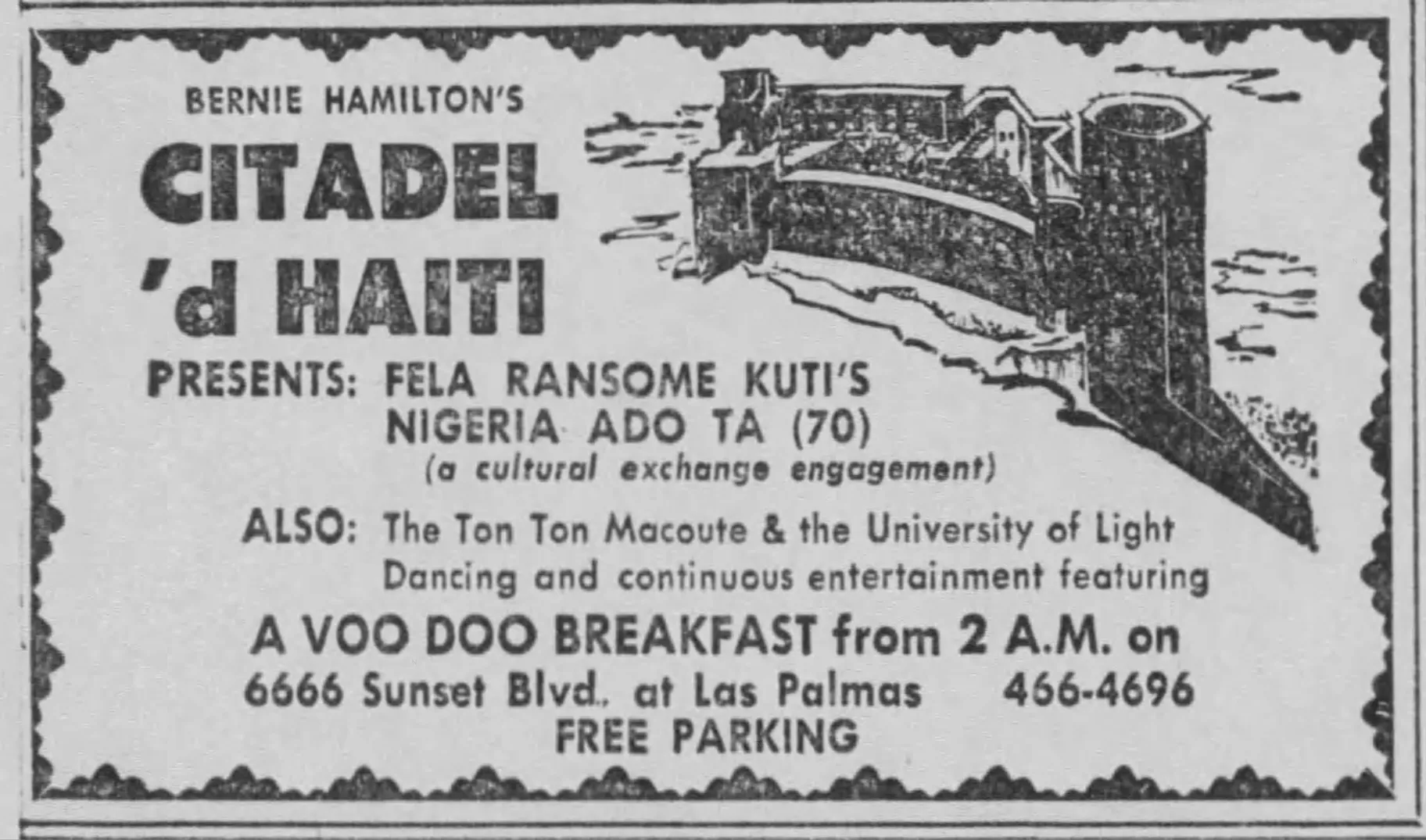

*cough cough* I wouldn’t know. But anyway, while Fela is out here undergoing this personal transformation, the rest of the group is still struggling. It’s been slow going as August turns into September… and then Juno Lewis comes back into the picture. He’s the one who brought Sandra to see Fela at the Ambassador show back in August. And he tells Fela that he’s just run into Bernie Hamilton, who is the brother of Jazz legend Chico Hamilton and a hustling actor. Well, Bernie had recently turned his own love of music into a funky little spot at the corner of Sunset Blvd. and Las Palmas called Citadel d’Haiti.

Advertisement for Citadel d’Haiti, featuring Fela, from September 1969.

Michael Barnes

By everyone’s account, Citadel d’Haiti was a unique place. They offered a palm-reader, a jewelry shop, a 2AM “voo-doo breakfast,” and an “acre of free parking,” which Hamilton turned into a Christmas tree lot in December. They also operated without an entertainment license, which meant Fela and his band could work there without the oversight of the local musicians’ union.

Novena Carmel

Hamilton offered the band $300 a week, under the table, to play three nights a week. And he also hooked the band up with a house to call their own. But by Fela’s account, Bernie’s place was a dump. It was late September, and the weather was starting to change. It was getting a little chilly by L.A. standards. And the house was so threadbare that they had to wear coats inside. Fela initially thought he should stay with the band out of solidarity, to be, y’know, a good bro. But in truth, almost immediately, he went off to stay with Sandra.

Michael Barnes

Ha! You know he just wanted an excuse to go to Sandra’s.

Novena Carmel

Probably.

Michael Barnes

But that was a good thing, because it was at Sandra’s that Fela finally had the musical breakthrough he had been seeking for so long. Even though he came up with the name Afrobeat back in Nigeria, the music he had been playing was still basically “highlife jazz.” But at Sandra’s – likely helped out by copious amounts of weed – he could now hear the sound of Afrobeat with perfect clarity. He sat down at the piano in Sandra’s house and began working up a new tune that he called “My Lady’s Frustration.”

Novena Carmel

This one was a song written with Sandra in mind. He was acknowledging how difficult things had been for them, and how much of a strain it put on her and on their relationship. And here is actually where the atmosphere of personal and political transformation he experienced in L.A. really starts to filter down into his art.

Michael Barnes

“For the first time,” he says, “I want to write African music.” He starts with a bass line, then adds the other elements. And instead of his usual habit of adding lyrics almost as an afterthought, he lets the music speak – using only wordless syllables, influenced by Yoruba chants, to anchor the voice.

Novena Carmel

By now, Fela had renamed the group from Koola Lobitos to Nigeria 70. And their appearances at the Citadel expanded from three to five nights a week, with a nice li’l pay bump to $500. The house swelled to more than 200 patrons for those weekend shows. And one night in October, he gets crazy and decides to premiere their new sound to the audience. He’s feelin’ it. And they break into “My Lady’s Frustration” for the first time, and the house erupts with energy. Everybody is dancing. Bernie Hamilton himself jumps across the bar with excitement. And the sound of Afrobeat finally comes alive … right here on Sunset Boulevard.

Advertisement for Citadel d’Haiti featuring Fela from October 1969, around the time of “My Lady’s Frustration. »

Michael Barnes

Now things are finally starting to catch fire. The band plays another high-profile gig back at the Ambassador on October 11 – this time as part of the musical lineup for the NAACP’s annual Image Awards. And Nigeria 70 continues to pack the Citadel well into November. By now, they’ve been working up this music night after night, and they are a well-oiled machine. An acquaintance of Fela’s, Duke Lumumba, arranges for studio time to capture the band in this moment.

Novena Carmel

And now, unlike back home, Fela and his band, with their new sound, are recording in a proper studio. Their earlier recordings were made under conditions of necessity – probably had the band all playing around one single microphone in one room.

Michael Barnes

Old school.

Novena Carmel

Yeah. But this is L.A. in the late ‘60s – and even a lot of the smaller studios could give the band an enormous sonic boost.

Michael Barnes

It really gives you an opportunity to appreciate the changes that Fela and his music have undergone, from the time of “highlife jazz” to now, at the birth of Afrobeat.

Novena Carmel

Right. It’s really a stunning transformation, when you think about it.

Michael Barnes

Oh yeah.

Novena Carmel

Why don’t we listen to some of that music together, so we can all hear the difference for a moment? I have a few tracks in mind, if you’re game.

Michael Barnes

Alright. Yeah. Let’s do it. What do you want to start with?

Novena Carmel

How about one of those Koola Lobitos tracks? Let’s start with “Mi O Mo.”

Novena Carmel

Right away everything hits you, right? And you can hear that 3:2 rhythm pattern, and the Ghanaian bell under the verse. There’s a density to the music in this period: you got those horns, and all those layers of rhythm, and that busy bassline. And you hear that in a lot of Fela’s early work from ‘64 to ‘68.

Michael Barnes

But with the first Afrobeat recordings, the tempo slows down, and there’s gonna be much more of an emphasis on the beat that drummer Tony Allen creates. Allen’s background as a drummer, raised on African Juju & Highlife as well as American jazz drummers like Art Blakey and Max Roach, gave him a unique style. And his ingenuity & creativity is a big part of what made Afrobeat’s sound so special.

Novena Carmel

Just leanin’ into it.

Michael Barnes

And you watch it, and it looks so simple, but it sounds so complex.

Novena Carmel

Okay, so, just to make the evolution crystal-clear, let’s cue up a track from the Los Angeles sessions. A number called “This Is Sad” will be good to hear. This one’s an instrumental, but I think that it really helps us zero in on the musical innovation.

Michael Barnes

This is already night and day from the beginning.

Novena Carmel

The first thing you hear is all that space.

Michael Barnes

So much spaciousness. Amazing.

Novena Carmel

Yeah. And a part of that is the improvement in recording quality … but Fela also has consciously reduced his music to the essential elements. He’s breakin’ it on down. And even though it’s at a slower tempo, it lands right in the pocket.

Michael Barnes

Yeah. Everything interlocks in this really beautiful way. The bass guitar takes its time, playing fewer and longer notes. The guitar work is clean and simple … and finally being able to hear Tony Allen’s drum work with such clarity is a huge part of why Allen becomes such a legendary drummer during his fifteen years with Fela. Just listen to that interplay between the hi-hat and the snare drum. My god.

Novena Carmel

It is money!

Novena Carmel

And you can easily hear one of Fela’s vocals from his early ‘70s period working over this, too, such as “Black Man’s Cry” or “Let’s Start.” So many of the essential elements are all locked into place. And, again, we’re talking about only a couple of years from “Mi O Mo” from Koola Lobitos to this, at most. But the dividing line between those eras was drawn right here in Los Angeles.

Michael Barnes

Shortly after these sessions, in March of 1970, Fela and his band finally returned to Nigeria. All told, they spent ten months in the United States. Fela returned home not just musically awakened, but politically as well. And when James Brown made his way to Nigeria in late 1970, he and his band stopped by Fela’s club, the Afro-Spot. And while Brown never has admitted it, both Bootsy Collins & David Matthews, Brown’s arranger, have admitted that they were influenced by the sounds that they heard there. And the interplay of all of those elements created the conditions for Fela to later become Fela Anikulapo Kuti, “He who carries death in his pouch”: the master of his own destiny … the Black President … and the legendary revolutionary artist that we think of today.

Novena Carmel

Yes. So, the next time you’re driving down Sunset Boulevard, go ahead and queue up a Fela Kuti track on the stereo, and crank it up a notch as you cross that intersection with Las Palmas. You just might enjoy a little energy exchange with the former location of Citadel d’Haiti, where Fela found his groove.

Michael Barnes

Oh yes.

Lost Notes is a KCRW Original Production. It’s made by Michael Barnes, Ashlea Brown, Novena Carmel, and Myke Dodge Weiskopf. Special thanks to Gina Delvac, Jennifer Ferro, Ray Guarna, Nathalie Hill, Anne Litt, Phil Richards, Arnie Seipel, Desmond Taylor, and Anthony Valadez.

Extra special thanks this week to Eothen Alapatt of Now-Again Records, H.B. Barnum, and Todd Simon.

MORE:

Lost Notes S4 – Ep. 2: Mojo on Trial: The Seedy, Greedy World of Ruth Christie

Lost Notes S4 – Ep. 1 – Tainted Love: Gloria Jones and the Half-Life of a Hit

Lost Notes: 1980 – Ep. 6: Minnie Riperton

Lost Notes: 1980 – Ep. 1: Stevie Wonder

Lost Notes S2 – Bonus: Power to the People

Crédit: Lien source

Les commentaires sont fermés.